There is a noticeable

trend among the moving images that have been curated for Inventing

Abstraction, 1910–1925 toward diminishing their significance as objects of

art, which undercuts the curators’ argument for the

emergence of abstraction as a “cross-media” creative tool. Currently on

display at the Museum of Modern Art’s Joan and Preston Robert Tisch Exhibition

Gallery, Inventing

Abstraction, 1910–1925 is a five month-long banner exhibition that attempts

to re-contextualize the appearance of abstraction by re-defining it as an

intrinsically cross-disciplinary movement rather than as a creative trend occurring

solely within the realms of painting and sculpture.

Anemic Cinema (1926) by Rrose Sélavy (Marcel Duchamp) playing alongside Duchamp’s Rotary Demisphere (Precision Optics) (1925), featured in the film.

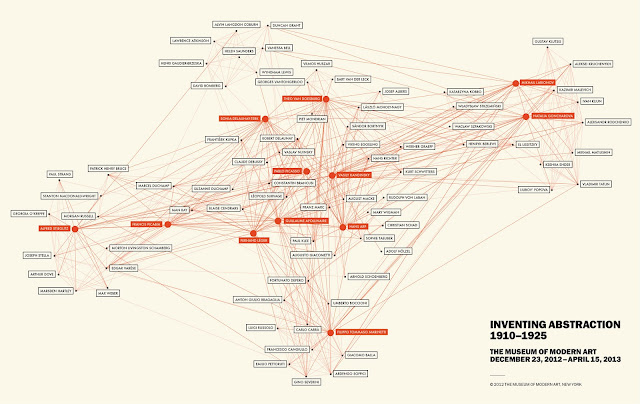

Before patrons enter the exhibition, they are greeted by an

enormous graphic that provides a visual illustration of the exhibition’s

primary thesis, which posits that abstraction grew out of the relationships shared

by artists who were working across a wide variety of media. (Inventing Abstraction, 1920-1925, 2012) (MoMA)

The curators' emphasis on the

cross-disciplinary nature of the movement yields an exhibition that is

ambitious in both its size and scope, including 350 works by 84 painters and

sculptors, poets, composers, choreographers, and filmmakers. Of these, nine are moving images. However in spite of the fact that all of the works in

the exhibition were originally shot on film, the curators have made the decision to install them as as High Definition QuickTime files that run

off Western Digital media players and are displayed either on Panasonic HD

digital projectors or on LCD HD monitors rather than projecting analog prints. The curatorial decision to display these films digitally cannot

be ignored, and raises a series of important questions: Did the curators believe

that the playback technology is irrelevant to the work, or that there is no

difference between a digital file and its analog source? Do curators have an

obligation to maintain the original characteristics of a piece, if it is

possible (even at significant expense) to do so? Why have the curators chosen

to present digital versions of these films, yet have insisted on presenting

original paintings rather than high quality reproductions?

Anemic Cinema (1926) by Rrose Sélavy (Marcel Duchamp) playing alongside Duchamp’s Rotary Demisphere (Precision Optics) (1925), featured in the film.

For museum-goers visiting the exhibition, the majority of

whom were families and young couples, the fact that these works were being

displayed using digital rather than analog technology did not appear to matter.

In fact, given that Inventing Abstraction is a blockbuster exhibition that is designed to draw in as many

visitors as possible, the absence of a loud film projector that would

have taken up valuable floor space probably helped the viewing experience by

making it easier for more visitors to crowd around the moving images.

However I believe that the decision to include movies rather than films does matter. Within the context of this exhibition, the curators’

decision to screen digital versions of these films contextualizes them as less

significant than the paintings and sculptures that they reference by signalling visitors to understand the films as being

less important and significant, and not unlike something they might be able to

watch on YouTube.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: Only a member of this blog may post a comment.